Review: A Small Light

I am once again going to deviate slightly from my usual premise of historical fiction to talk about another sort of historical narrative. I want to talk about A Small Light, the Hulu miniseries about Miep Gies. She was one of the people who hid Anne Frank and her family during the Holocaust.

The hot take: Watch it if you want to see a little-known perspective of a well-told story. Watch it if you want to see how ordinary, decent people rose to the challenge in the darkest times.

It’s difficult to find new ground to traverse when it comes to Anne Frank. Her diary is the second-best-selling book in the non-fiction category. Of all time. Second only to the Bible. That means pretty much literally everyone knows about her. Probably a lot about her. There are books by and about people who knew her. There are several movies. The Secret Annex in Amsterdam is one of the most visited tourist destinations in the world.

So how did they find a new way to tell the story? They found a new perspective. A minor character, without whom we wouldn’t have the story at all.

Miep Gies was a secretary at Otto Frank’s company. She helped the Franks, the van Pells, and Dr. Pfeffer go into hiding. She was their main point of contact. She saw them almost every day. She devoted most of her time to scraping up enough food for them without attracting suspicion.

When the Gestapo came and the Franks were arrested, Miep saved Anne’s diary. She didn’t read it, just put it in a drawer to save for Anne when she came back. She later said she was glad she didn’t read it, because she would’ve had to destroy it to protect the people in it. Can you imagine a world in which is Anne Frank’s diary didn’t survive? I don’t want to.

Miep is a hero of this story. She’s a protector. And I know that I, for one, knew almost nothing about her until this miniseries.

Ordinary people

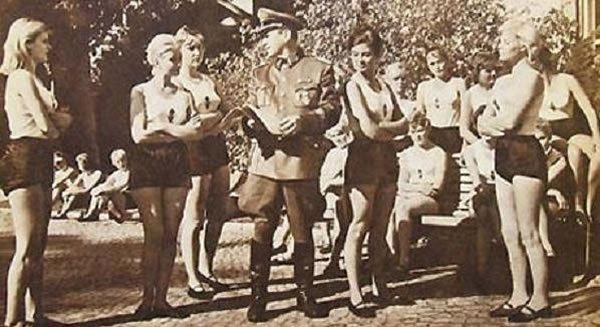

An aspect that the show covered very well, which many other renditions of Europe in World War II struggle with, is the way normal people reacted to Nazi rule.

So many regular people didn’t like the Nazis, but it was their new reality, and they adapted. They joined the Party so they could keep their businesses. Their own hunger, loneliness, fear, and desires overwhelmed their principles. They wanted to live and be happy and safe. And they told themselves they were powerless to change anything, so it hurt no one to go along.

Miep shows us that you don’t have to do that. Even if you have to pretend in public, you can still do something. You can do as much as you can.

She was a normal person. A secretary. She is a wonderful example of ordinary people doing extraordinary things in impossible times.

In the face of the insurmountable struggles that we face in the world, it can feel too overwhelming to even try to make things better. How can we begin to even make a dent in all the problems? But then you look at Miep. She opposed the Nazis, not by becoming a spy or trying to overthrow the government – which would feel too big and scary for most of us to even consider – or making grandiose gestures that would’ve made no difference and only gotten her killed (see A Hidden Life).

Instead, Miep helped the people around her. She couldn’t save the world, but she worked her ass off to save seven people, to save their whole worlds.

The face

It is devastating that only one of those seven people survived, despite all the risk and heroic effort. But because Otto Frank survived, and because Miep saved in the diary, millions of people have gotten to read it. It’s impossible to know the impact Anne’s diary has had on the world, but we know it has given a face and a soul to the victims of the Holocaust when the numbers are too big to imagine. It makes something unimaginable feel very real. Time and time again, I try to imagine not feeling the sun on my face or breathing fresh air or never really being alone for two years. And I can’t.

But Anne, an ordinary, bright, imaginative, extraordinary teenage girl, did it. And it is unimaginable to think that she and everyone else in that Annex, after hiding for all that time, then faced the most horrific conditions imaginable in the camps.

I read in the Sisters of Auschwitz that when Anne and her sister Margot were separated from their mother, they lost their will to live. They simply waited to die. For some reason, that is one of the hardest parts for me to hear about the story of her life. The Nazis not only killed her, but they destroyed her spirit first.

That is something the minseries demonstrates very well: they show how alive and bright and strong Anne was, and then they show her being shoved into a truck and taken away, never to be seen again. It’s horrifying. But I’m getting too dark. I’m sure these are thoughts that we’ve all had.

Spitfire

Sometimes I became frustrated with how hotheaded Miep is. You can’t just yell at Nazis in public and expect to stay alive. And she was not in a situation to be taking those risks, when so many people were depending on her for survival. I wonder if the real Miep was like that, or if her fiery spirit was played up for dramatic affect. She seems too smart to be letting herself get so carried away in dangerous situations. But it’s a fact that Miep marched into Nazis headquarters the day after the arrest and tried to bribe the Nazis to release the families. It didn’t work, obviously. What a bold, almost suicidal move. Yet she survived.

The day after the arrest, Miep marched into Nazis headquarters and tried to bribe the Nazis to release the families. It didn’t work, obviously. What a bold, almost suicidal move. Yet she survived.

And because of all these moments of chance and grace and risk, this story survived. And because of it did, we have a little bit of hope that we too can be a Miep. Anyone can, if they decide to be.