Bizarre things I want you to know (about Lebensborn)

There’s an astonishing amount of research that goes into writing a historical novel. If I were to put everything I learned in my book, it would be at least a thousand pages long.

A lot of fascinating historical information just doesn’t do enough to serve the narrative of my particular book. Things that were too bizarre and twisted to be real, and yet they were.

Now I know these things, and I can’t un-know them, and I can’t just not tell people, so I’m sharing them with you.

Here are the weirdest, most surreally disturbing anecdotes from Lebensborn, the Nazi maternity program.

“Every mother of good blood must be sacred to us.”

—SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler

Lebensborn was started in 1935 as SS leader Heinrich Himmler’s pet project. He was also in charge of running the Holocaust.

Many Lebensborn pregnancies originated when the boys and girls on Hitler Youth camping trips managed to have rendezvous. The same happened when young men and women went to their Landdienst or required one year of “land service,” where they worked on farms.

Contrary to what a lot of people assume, there was a mix of married and unmarried mothers in Lebensborn. People have asked me — really really often — why a married mother would enter the program. Usually, it was to suck up to Himmler. Other times, it was because they believed they would get superior care and enjoy a staycation vibe.

These perks were especially appealing when rationing took effect — Lebensborn was one of the few places where coffee, chocolate, butter, and pretty much any food that was available in the 1940s, could be found. For everyone else it was potatoes potatoes potatoes. With linseed oil.

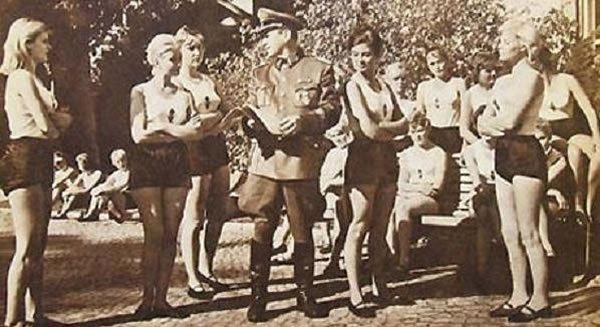

What looks to be a pretty standard (and gross) mating ritual — SS officers getting with teenage girls from the Hitler Youth.

Later in the war, married women sought refuge in Lebensborn homes as Allied troops advanced, since they were away from the cities and equipped with better food — and better everything in the face of massive shortages.

Some mothers kept their babies, while others left them to be adopted by SS families. When a mother decided to keep her child rather than giving it up for adoption, Lebensborn documentation called it “taking their parcels home with them.”

Many of the homes were properties stolen from Jewish people. One was the former home of Thomas Mann; he was appalled at the use it was put to.

There were ten homes in Germany. In total, 8,000 children were born in these homes.

Babies got two hours of fresh air in the afternoon, rain or shine. They were also bathed twice a day.

Because of Lebensborn’s poor reputation in the early years, many SS families refused to adopt Lebensborn children. This led to overcrowding in the homes, with substandard care (like nails and wires somehow ending up in broth) and high infant mortality rates (8% when the norm was 6%). Lebensborn covered all this up.

Unmarried mothers were sent to homes in different parts of the country than where they were from to prevent them to protect their reputations.

Babies were given candlesticks at their baptisms. The candlesticks were made by Dachau prisoners.

In the early years, mothers would sneak into town with their babies to have them christened. Lebensborn had a baptismal ceremony of its own and had no interest in its elite babies being Christians. This was part of the reason why outings were restricted in the later years. Another reason was that people hated Lebensborn mothers. In one incident, two women were badly beaten by townspeople. After that, visits were restricted.

Lebensborn ran until the very end of the war. The original home, Steinhöring, was located in Bavaria, making it one of the last Nazi strongholds.

When American soldiers arrived at Steinhöring, they were shocked to find the attic of a large house filled with neglected babies and toddlers and one or two nurses who were not happy to see them.

Most of the Lebensborn employees had fled beforehand, hoping to avoid affiliation with a Nazi program.

I find this image especially disturbing for some reason. I don’t know if these were mothers or nurses — but mothers were almost never photographed to preserve their anonymity, so my guess is nurses.

Another time, I’ll tell you about the fathers — called “originators”— the employees, the children, and the homes outside of Germany.

Hope you’re as creeped out as I was!